The Center Can't Be Held

considering the field of centers

The group house I live in has no center. There is a kitchen, where people will gather to cook food, and sometimes a few of us will sit at the island together to eat. There is a dining room, which we used for house dinners every so often when I first moved in, but we haven’t done that in a while, for no clear reason. There is a back yard containing a fire pit, which becomes a friendly gathering point when we host parties. There is a room we call the TV room, or half-seriously the parlor, where a few of us will occasionally gather to watch a movie or read quietly. And there is a living room, where recently I’ve been having friends over for meditation on Sunday mornings.

During those sessions, we sit in a circle and rest our partially-closed eyes on the rug, which occupies the center of the room.

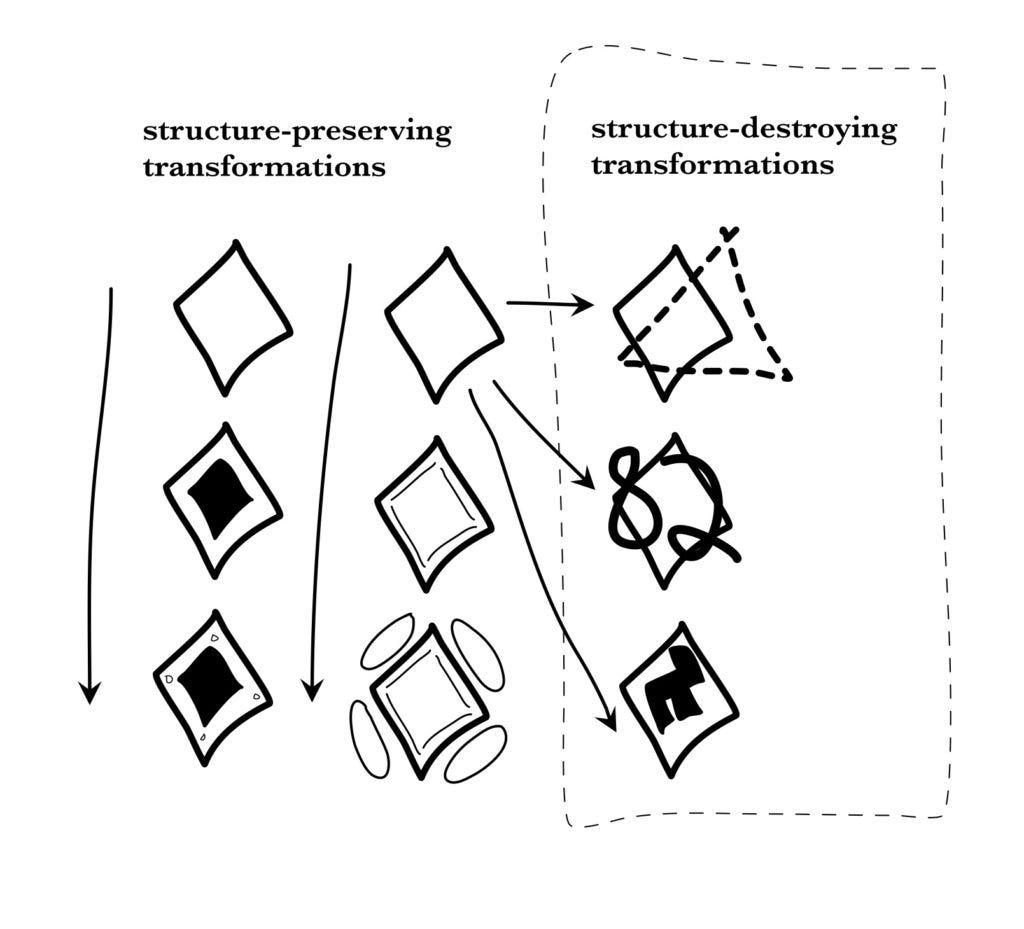

The pattern of this rug reminds me of one of my favorite essays by one of my favorite essayists, Sarah Perry’s “Deep Laziness.” The essay explores the work of the architect Christopher Alexander, who wrote about beauty as something objective that could be broken down into identifiable patterns. It contains this illustration:

And this passage explaining it:

The structure-destroying transformations are recognizable as mess: competing orders don’t allow for a coherent, harmonious whole. They are not peaceful to look at, and further attempts at structure-preserving elaboration will only “preserve” an ugly, messy structure. On the other hand, simple as they are, the structure-preserving transformations have a bit of quiet ease. You can imagine going on like that, adding dots here and lines there, just as needed, until it is quite elaborate. As long as each transformation preserves the underlying structure, it will retain its wholeness and beauty. They are not based on any pre-existing image; rather, they are “easy, natural steps which arise from the context (ibid. p. 439).” Even decay can be structure-preserving, when the decaying structure was produced by this process: decay reveals underlying levels of organization that are attractively harmonious, because they formed the basis for the elaboration of the whole (e.g. bones, shipwrecks).

What is this underlying structure? It is the “field of centers,” made up of “centers,” a Christopher Alexander term I have written about extensively, and about which my thinking changes each time I write about it (hopefully becoming more correct). A center is an aesthetic concept that is somewhere between geometric, phenomenological, and mystical. It is defined recursively – a center is made up of other centers, and in turn makes up other centers (hence the “field of centers” as the primitive). Centers are the basic building blocks of beauty, except that they’re rarely shaped like blocks. If you look at any beautiful thing, a building or a tree or a hand tool, it will possess strong centers. In the diagram above, the diamond is a center, and each embellishment (and the spaces between, when they form good shapes) is a center. Each new whole, after each structure-preserving transformation, is a center. Centers are “things” – shapes, plants, doorways, furniture, faces, eyes, motifs, bounded spaces, boundaries, clouds. The centers form the seeds for the next structure-preserving transformation.

It’s interesting to me that when we meditate we sit the way we do, all facing inward toward the field of centers that is the rug, without ever having talked about it. There is something natural about forming a circle and facing in. Considering the kind of meditation we’re doing, there’s a symbolic fit here: we’re collectively exploring an experience of emptiness, and we position ourselves in such a way that a child without any concept of meditation might see us and kind of get that. The rug is an unintrusive, undistracting resting place for a pair of eyes. When people come who haven’t sat with us before, they are likely to make comments about it in the discussion afterwards, reporting that its pattern seemed to undulate or become unusually vivid.

I’ve noticed that the group embodies a high degree of sensitivity to the shape of the circle. If it becomes too weighted on any one side, someone will adjust to balance it. If someone enters late, they will add themselves in a way that preserves the structure, and if this is impossible then the others will instinctively move to create the needed space.

When it first occurred to me, this thing about the house having no center, the thought triggered an immediate contraction. What am I doing, something in me said, living in a house with no center? Can such a place really qualify as home? I felt a density of sensation around my torso, a dark, billowing grossness, the sort of response I’ve learned to take as a good sign, a sign that I’ve poked some piece of conditioning that will probably be fruitful to explore. As I moved toward the center of the response, it quickly became clear that I’d been devoting a lot of mental energy to various attempts to fix this felt absence—not just in my house, but in my life. Something in me was pattern-matching the “centerless” feeling as a bad one, and I found myself searching airlessly for a compelling center to latch onto: an almost subliminally rapid search through mental and physical space that felt a bit like my life flashing before my eyes. Judging by how quickly and effortlessly this search unfolded, it’s something I’ve practiced a good bit.

I was forced to dismiss each candidate that came up. My family? It’s a nice thought, but can they really be the center if I’ve chosen to live thousands of miles away? (Or maybe they are, and I’m making a terrible mistake?) My house? See paragraph one. Uh, meditationy stuff…? No, that’s more like a toolbelt: best kept to one side and reached for when appropriate. My writing? No, remember, we tried that, it made us miserable and we had to stop doing it? Romantic partnership? I’m single… My body? It’s too… single…

I want to be fair to myself here. I don’t think I’d been consciously thinking that there was supposed to be a single dense core of meaning and beauty in my life, and that I only had to find it in order to feel okay. Nevertheless, when I looked at my immediate reaction to noticing that there was not a single dense core of meaning and beauty in my life, it seemed like emotionally I was holding a different view. It seemed like what I believed at that level was more like, yes, of course it’s fine not to have a single dense core, as long as you’re always actively working to create one.

In other words, as long as it wasn’t really, fully okay.

Seeing this belief in action caused a large rush of blood to my head, and as I journaled about it afterwards, a handful of concepts I’ve been mulling over for years clicked into new arrangements. For instance, Ngakpa Chogyam Rinpoche talks about the dynamics of dualism in terms of habitual attempts to establish and secure what he calls “reference points.” I’ve come to find this a highly resonant frame, but I still find “reference points” hard to visualize in a useful way. The language of centers feels more intuitive, and it’s been making it easier to drop some of my searchfulness and just fuck around enjoyably in the roving field of centers.

Also, “the field of centers” is a nice visual example of “the nonduality of form and emptiness,” Buddhism’s (and especially Dzogchen’s) main theme.

As I describe this, it kind of sounds like I’m just regurgitating old metaphors with a slightly different tilt. What it feels like from the inside is different. It feels like noticing that the metaphors aren’t—metaphorical—in the way I thought they were. This sort of thing seems to happen to anyone who engages with a tradition for long enough, and it is very weird and interesting and I wish I had a better model for what’s happening. You’ll hear something a thousand times, and the thousand-and-oneth time you think, oh, wait, you meant that? Or, wait, you meant that? It can be and often is about the simplest of things. A friend told me about an insight he had listening to a meditation teacher speak: “It suddenly occurred to me that when people say ‘just be in the present moment,’ they actually mean it. It’s a real thing you can just do.”

If I had to encapsulate what feels new here, it’s that there’s a strongly spatial dimension to reference point fixation that I was missing, even though I was looking for it, somehow. Maybe looking for the center of my house clarified this, whereas many of the other centers I’ve tried to fixate have seemed to occur spatially in my head region?

Fixating a center is a kind of sensory gesture that I’m finding pretty easy to do on command. The easiest way for me is to look at something—here, I’ll take this Nalgene bottle on my desk—and briefly convince myself that it’s the most important thing in the universe.

Almost immediately the bottle begins to take on a surreal density. Its outlines sharpen; its blue tint becomes slightly magical. As I turn up the centerness knob, it starts to seem more distinct, more disconnected from its surroundings. Soon this is no longer “my” “water” “bottle,” but some sort of dark totem dredged from an ocean that will never be found on maps. It seems distinctly non-ordinary and like it doesn’t quite belong in the same category of stuff as its surroundings. My body, if I bring it back into the picture now, seems defined by its spatial relationship to the bottle; there is a slight tingle in the closest parts of me, like a gravitational pull, and the space between us seems charged with subtle currents.

When I relax whatever I’m doing here, there’s a feeling like a wave touching down, and the bottle merges back into its context.

It’s fairly easy to see why making a water bottle the steady center of the universe would not be that much fun. But the assumption that there should, at any moment, be a center of some sort is harder to dismiss. Sometimes people try to make or find centers like this and call them things like God, or The Good, or Truth, or Awareness, or Being a Good Person, or Pursuing My Calling, or Saving the World, or Achieving Buddhahood for the Sake of All Sentient Beings.

Moving out of egocentrism—moving the center out of the self—as in prayer, is extremely powerful. I heartily recommend it. What I’m pointing to is the stance that you gotta keep that attitude steady, or steadily work toward that steadiness it if you aren’t in it. This stance is ultimately unsustainable—David Chapman describes why in his description of “eternalism”, which I think roughly maps—and it sounds obviously dumb when I put it into words, but that doesn’t keep it from being easy to slip into.

For me, the belief in an ideal center seems to arise when I have more energy in my system than seems manageable. I’ve been really enjoying coding lately, which is new for me, and it’s triggering feelings of “is this curiosity safe” and “is this the Real Me"? There’s a theory I find cycling that exciting new activities bear the risk of crowding out other important stuff—of becoming structure-destroying transformations. It seems to be founded on an outdated sense of my energetic capacity and of the flexibility of my structures. Mostly what’s happening is I feel thrilled to have found a project I like this much, and that excitement is spilling into and revivifying everything else.

Imagine a moth who uses the allure of one lightbulb to escape the pull of the last—and then a third lightbulb to escape the pull of the second one, and so on. He’s clever, within the bounds of his ruleset. But he’s obviously missing something, which is the option of flying around without flying toward lightbulbs.

On the face of it, it might seem like a fixation on having a center would lead to… establishing a strong center.

But this isn’t so. It more likely contributes to ambivalence. As I see it, this has to do with the structure of craving.

Craving, the way I think about it, is un-usefully complicated wanting. It’s when wanting is routed through a fear of not having, which seems like the same thing but isn’t. (See my discussion of corralling here.) A major downside of doing wanting this way is that it creates a sense that getting what you want is actually existentially unsafe, and you should secretly avoid succeeding. Craving involves a narrowing around the view that moving closer to this thing is all that matters—which implies both that you’d be crazy not to be moving closer, and also that once you get the thing, you’ll have destroyed your only source of meaning, i.e. the distance between you and the thing. The hidden philosophy of craving is, “better to seek than to find.” (And definitely don’t relax.) A person engaged in craving might theatrically proclaim that making great art is the most important thing in the world, but find themselves strangely unable to finish a poem. Or they might affect an inconsistent indifference toward the person they have a crush on, knowing that to be openly interested would risk destroying the crush, one way or the other. Craving is a creative way of keeping the thing we think we want at a safe distance, in order to avoid being changed by it. It’s something we all do some of the time.

The craving for a solid, unchanging center is fueled by fantasies of simplicity. It assumes the problem is overwhelming complexity. (It wants there to be just one problem, because it assumes problems are unenjoyable.) “One day I will find the job that saturates me in joyful ever-increasing challenges every day, and then there will be no more difficult choices to make about work ever again.” “One day I will find a partner who fascinates me so unrelentingly that there will be nothing for us to do but gaze into each other’s eyes and ask The 36 Questions That Lead to Love until the sun burns out.”

But what if my boss asks me to do some bullshit I hate, or the girl I’m dating turns out to connect deeply with Steely Dan? A terrible question may arise: what if this was the wrong center?

And then it’s time for a new lightbulb.

The pattern already felt looser after I’d brought some awareness to it. After that I asked myself some simple questions. Is there a single thick center for me to orient around? Right now, not really. Is there usually? Hasn’t seemed to be for a while. Do you want there to be? I don’t know. Maybe not? Maybe sometimes but not all the time? How can you know? It seems like one of those things I can’t make a rule about.

Let me get this straight: you don't know what it is. You don't know where it is. And we can't get any?

Put that to one side.1

So now, this feeling bad when you notice you don’t have it. This is… interesting? Useful? Something you want to keep doing?

Oh.

This inquiry released a lot of joyful energy, as finding carefully hidden options tends to do.

If there’s anything that seems different on this side of the felt shift, it’s that centers are seeming more abundant and less menacing. Like, look, maybe you noticed?: I started this essay by saying that my house has no center, and then, as evidence of that, I named six. Those centers are contextual and transient, but why exactly should that be disqualifying? Minus the view that one of them should be existentially supreme, that everybody must sometimes be gathered in one place, with one shared focal point?

I’ve been playing with the phrase “good-enough centers” as a way to remind myself that the aesthetic pleasure to be had from finding and elaborating centers does not rely on finding The One Center to Rule Them All. I suspect one reason this tangle is easy to fall into, for me, is that the dance of good-enough centering is the dance of much great art. In its absolute laziness it produces stunning mosaics that we can’t help wanting to preserve. The dance was so good we go clumsy-footed in our desperation to repeat it, forgetting that it was only one series of embellishments.

Funny thing about these essays, they often begin with me feeling totally stuck—sometimes for only a few minutes, sometimes for days. There’s some vague thing I want to write about, but I can’t figure out how to get there. I have a set of stray thoughts and no sense of how to string them together, no sense of what’s central and what’s incidental, no understanding yet of which thoughts make up the set. The temptation is always to look at the thicket and conclude, I guess I can’t write about that, then.

Invariably something changes when I take one of the thoughts and write it down.

It seems to be missing something.

I know I’m “in it” when possible elaborations exceed my ability to include. I’m forced to drop an idea because I can’t hold it while I write this one, and wait, now that this one’s here, that one no longer fits. What I thought would be the center falls in on itself, becomes an elaboration around a different center that was hiding smoldering in the ashes left over from a different essay entirely. This feeling of being in it, of elaborating without knowing where I’m going, sensing only that I haven’t reached an end yet, is one of the best feelings I know. I think this is why writing used to scare me so much, and still sometimes does; when I’m in it, it can seem to want to become the whole center, the Big One, and to metastasize until it crowds out my own structural preservation.

And it’s an affront to my intelligence, this process, every time—or at least, an affront to what my intelligence thinks it is. Because my initial thought was always mostly true. I couldn’t write about that thing. And maybe I never will. When I look for the center in the pieces I’ve assembled, it’s always somewhere else.

Roaming freely through a field of centers, able to stop and enjoy any one, but never trapped by any one...what a powerful image!

This resonates with the feeling of a lazy Sunday, enjoying the downtown strip with family...there is the bookstore, the toy store, the restaurant, the park, the playground...each of them becoming a center to be enjoyed for a natural wave of energy, and then released back into background.

I never was a fan of Steely Dan until only a few months ago. I flipped through radio and encountered a replay of Casey Kasem's American Top 40 from 1981...they were playing Time out of Mind, and I was, "wow, that's a great break!"

Now, I've loved the work Keith Jarret for decades, and for the song Gaucho, they stole from the best...Keith Jarret sued and won songwriting credit on that song. Anyway, while I was on retreat in the woods, Gaucho constantly played in my head, beautiful in its expression of frustration: "No, he can't sleep on the floor! What do you think I'm yelling for? I'll drop him near the freeway...doesn't he have a home?"

I can tell that this is an essay will read at least thrice. Thank you!

I loved this! (and will definitely be pondering it for a little while to come.)