I’m thinking about what I will tell you today and some part of me “activates.” It seems to believe the things to say are “out there” somewhere, outside the window, by the uh, pond (?), and that they’ve got to be hunted down, shot, fetched, bagged, affixed to plaques in anticipation of review. My body seems to be preparing me for a short sprint down a path. It feels in the initial moment like the sprint is away from something—as if this were a game in which a creature much larger than me is unleashed to chase me for the delight of a small audience. I always have to remind myself that you are on my side, that there are no real sides, that you are merely me stretched out along various vectors and vice versa.

These days I tend to think of myself as more relaxed than most people I encounter—but am aware of the irony that this is only because I “work on” relaxation daily, somewhat assiduously, and begin to lose it if I take a long break from practicing. Was I drawn to meditation (when most aren’t) because I had a harder time relaxing than most people, or have I been able to sustain meditation (when most don’t) because I have an easier time of it? All I know is after five years of setting aside time for (reductively speaking) relaxation every day, it still feels like it’s only just coming into availability, or at least a new kind of availability, mainly now that I’ve taken up the Qigong practice of breathing into an imaginary balloon in my lower abdomen, just below my navel, a space called variously the hara or the lower dantian. It is helpful while doing this to fix my gaze on an empty point in space and suspend my tongue partway between my teeth and the roof of my mouth. The effect is fairly quick, no more than ten breaths: my posture loosens, sensations start flowing freely from head to perineum, I feel confident and alert. I agree, it really doesn’t seem like things should work this way.

Mind-body dualism is false, but maybe because the fiction is deeply structured in me, my development as a practitioner seems to have been skewed toward relaxing the mind and “thinking” before learning to relax the body—to get a lot of the psychedelic vividness and intense rushes of insight without feeling very good or present in my abdomen, my trunk. Because (I think) I was practicing an open, non-concentrative form of meditation, this didn’t lead to anything so bad as what I’ve heard can happen to some who practice so-called “dry” vipassana (concentrative insight without a base of embodied connection)—I’ve had no psychosis, nothing that would qualify as a “long dark night of the soul” as described by the pragmatic Dharma crowd—but the overall expedition has certainly had brief periods of (possibly unavoidable) derealization, and in retrospect some garden-variety megalomania that probably wasn’t great for relationships. I’ve spent the requisite amount of time guessing I was permanently Enlightened, walking around rooms marveling at the splatter of a few exploded concepts. It’s been helpful and grounding lately to read Rob Burbea, who toward the beginning of his book Seeing That Frees, which I’m reading with the Evolving Ground book club, advises developing samādhi, “unification of mind and body in a sense of well-being,” before pursuing deliberate investigative insight.

Over the long term, repeated and regular immersion in such well-being supports the emergence of a steadiness of genuine confidence. We come to know, beyond doubt, that happiness is possible for us in this life. And because this deep happiness we are experiencing is originating from within us, we begin to feel less vulnerable to and dependent on the uncertainties of changing external conditions. We may also find that a relatively frequent taste of some degree of samādhi helps our confidence in the path to become much more firmly established. Gaining confidence in these ways will have a profound effect on the sense we have of our own lives and their potential, without making us aloof.1

Stellar advice!

But so this “activation” I started by talking about—one way to describe it, functionally, is as the byproduct of a belief: a belief that a certain kind of communication requires inhabiting a certain psychophysical range. Call it a vibe. We could think about culture as a medium through which vibes are transmitted, but more interestingly we could call it a medium through which we learn the vibes that are recommended/appropriate/enforced for any particular activity. When I watch live music I find myself attending mostly to how the musicians stand, how they breathe, their facial expressions, how and whether this all matches up with the sound they bring into being. A great musician conveys to me, through sound and stage presence, the in-the-moment finding that one can make the most artful and intricate gestures from a state of general physical relaxation, in fact best of all from such a state.

Our culture isn’t generally doing so good with this vibe transmission thing. My sense is that states of relaxation are generally and maybe increasingly distrusted, discouraged, not to mention actively interrupted by the Device. It is universally agreed we live in times of crisis, a word we use or used to use for situations you must not relax about until they’re averted or passed through. The platforms have their own reasons to up-regulate us, since they know our attention can be tunneled (and so funneled) more easily if we lose the sense of space. Constant up-regulation makes us less collaborative and rots our natural intelligence, but this can hard for many of us to remember, or even believe, against the AI-tuned drip-torture of the feed. The guy/app/movement who’s shouting at you to hurry up and do something is either ignorant about the effects of stress on quality of action, or is prioritizing something other than the quality of your actions. This applies to the guys in our heads, too.

A huge amount of “spiritual teachings” are just relaxation instructions, really. Teachers downplay this or at least avoid saying it in every sentence for a few reasons I can think of: 1) it’d be boring; 2) telling someone to relax who doesn’t know how is not that helpful; 3), most people are not particularly interested in relaxing as such, don’t consider it profound or vital or worth investing time in, perhaps because those who really need the instructions don’t have any recent experience of what sustained relaxation is actually like. (This describes my experience pretty well.) Relaxing can be an elusive, slippery thing, there are many styles of relaxation, and I don’t mean to suggest that any of them are simple to teach, or learn. Even when you do catch a wave of “it,” it’s surprisingly easy to forget “it,” or mistake “it” for transcendence, or get so eager about “it” that you subsequently drive it away. Over time, as the periods lengthen, a common pitfall is that you start to think of relaxation as something you can and should control, and so the cycle repeats at a different level.

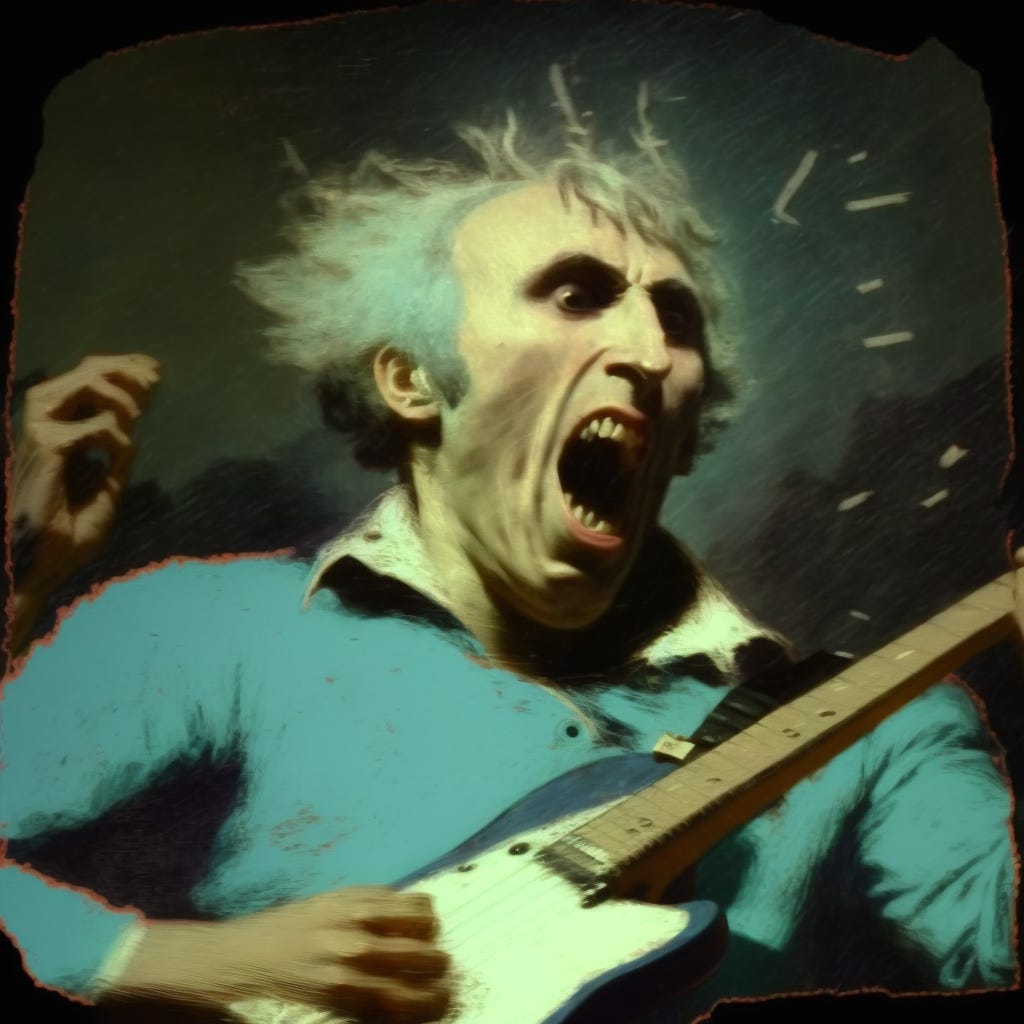

Writing has always felt hard on my nervous system, has always pulled me out of relaxation, and I’ve been wondering lately how much of that is an inherent and necessary strain of the activity (unnatural posture, sustained cognitive involvement, eyestrain) and how much can be attributed to culturally and generationally transmitted vibes around what the essayist J.D. Daniels once called (adapting Wordsworth) “the emotion-recollected-in-tranquility racket.” It is hard to deny the beauty of languages that performatively destroy their hosts, like a rocker smashing her guitar before the lights dim, which still seems to encapsulate a primary aesthetic in American art. And I’ve noticed a worry in myself and others that relaxing will rob us of having anything to say, as if the infinite varieties of failing to relax have become our master narrative, the one without which we don’t know how to think or tell a story. I find myself fantasizing toward a kind of writing that would be like sliding all my weight along a foam roller, where the main sound would be the release of realignment, pops and gasps of space opening between vertebrae. I suspect this wouldn’t be obviously recognizable as literature, but that might be a point in its favor.

The vibes are always transformable, anyway, and they’re always ours to shape. If you can’t find the vibe you want in your medium, you can import it from another. (One way of conceiving spiritual teachings: they’ve got the most broadly transferable vibes.) I’m starting to understand that you can do quite a lot for people—and incidentally, a lot less to them—simply by doing whatever you were already gonna, while remembering periodically to breathe into the balloon.

If you’re enjoying this newsletter, please consider sharing it with >=1 other person.

Burbea, Rob. Seeing That Frees: Meditations on Emptiness and Dependent Arising (pp. 41-42). Kindle Edition.

This essay helped me see some things with fresh eyes. Thank you.

Laughed hard at headline + image.

Than appreciated the nuanced thought.

Than laughed again at "I find myself fantasizing toward a kind of writing that would be like sliding all my weight along a foam roller, where the main sound would be the release of realignment, pops and gasps of space opening between vertebrae."

Really cool text!

Gotta breathe into that balloon.